Ecology of an Environmentalist

Recently, at a workshop about environmental justice, I found myself wondering if my environmental creed also included social justice. And why had I became an environmentalist in the first place and not, say, an advocate of the poor? To find out I would have to go back to that other life, the one with no catchy slogans, no rousing mission statement, no words at all even, only pictures flickering in my mind.

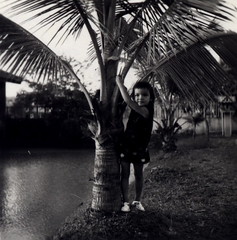

The pictures show that I lived by the side of a pond covered sometime with a carpet of vivid green duckweed and sometimes not. The words would tell you that I lived in the middle of a cosmopolitan city called Bangkok and that I went to school to learn the history of England because of my English heritage. The pictures tell the story of tadpoles.

The tadpoles had grown legs and were living in the shallow end of the pond. That these black seedpod bodies, smaller than my little finger would then become tiny toads was a delight that was mine alone. I took care not to muddy the water so that I could watch them. And though I did not feel compelled to commit my observations to paper, as I did all the "important" events of my life, I visited the tadpoles everyday until they were gone from the pond.

Perhaps it was then that I became an environmentalist for I had learned the importance of habitat and the undisturbed tranquility needed for these delicate transformations.

When a huge fish died and floated to the surface, my Aunty Sakorn came to the banks of the pond and studied the situation. A tree full of pods of some sort had branches that had grown so heavy it trailed into the water and was making a huge mess. She ordered that it be cut away from the water and that seemed to cure the problem of the dead fish. Thus, I learned, that the ecology of the pond was our responsibility, for it was in our front yard. In fact it ran under part of the house. Our shower water emptied into it. I knew because I had crawled under the house and followed the pipe coming out of the floor to where it stopped above the pond. Shower water, at any rate, was okay for the pond.

In the kitchen, the outdoor one at the back of my grandparents' house, there were a bevy of toads to watch, hopping along the cement floor, climbing on top of each other and generally being a warning to children about warts when I went to pick them up. And when I wouldn't heed the warning, I was told to just leave them be for they had to get on with their lives too. In that Buddhist/animist sensibility that informed my world, there was to be respect for all living things for you might well come back as a toad yourself. So there.

There were other creatures to observe too. Geckos clustered at the ceiling light in my room, centipedes arrived on the driveway, turtles on the grass, and red fire ants on the fence. Crows, beetles, salamanders and the occasional spine chilling, breath stopping appearance of a snake populated my world. Fear of snakes haunted my childhood, but we only killed them if they came into the house. Snakes prevented me from going too far into the tall grass in the empty lots that peppered my neighborhood.

On my bike I rode up and down our street looking for children to play with. The houses being built in my neighborhood were modern, split level 60s style homes with sunken living rooms, air conditioning and lots of glass windows. They were rented out to foreigners.

My American friends lived in such a house, next door to an empty lot. One day we decided to venture into it. The three of us, Kim, her brother King and I walked to the edge of it and paused looking at the tall grass.

"What if there's a cobra in there?" warned Kim, who was the eldest.

"Well then I would just put on my swimming mask so he couldn't get me," said King.

"But you don't have your mask with you. Are you going to say "please Mr. Cobra, can you wait a minute before biting me, while I go get my swimming mask?" Kim pointed out.

King and I laughed and then we walked in anyway. There was a path and small trees that obscured the boundaries. It was our own private little jungle. Soon the path opened up into a dirt clearing and we came upon a small wooden house raised off the ground, on stilts, about waist high. On the porch sat a woman smiling at us. She was wearing the traditional batik sarong that all the maids at all of our houses wore. Only there was no big house on this lot. And she was not alone. With her was a baby the color of milk chocolate.

The Thais do not eat chocolate, or at least they did not at the time. They thought it tasted bitter. Not until the next generation, when imported chocolate became more common and it was prestigious to offer it to their children, did those children then develop a taste for chocolate. We three, however, had Western palates and were already addicts. We delighted in this baby and made a great fuss over her pretending to eat her up. The baby laughed with pleasure at all the attention.

My Thai family was not the color of chocolate. They liked to stay out of the sun, so as to remain pale and not be mistaken for peasants. This desirable distinction was lost on me, especially since my British mother spent her weekends sunbathing so she could have a "suntan". I did know that the browner the kids were on my street, the more likely they were to be poor. I could tell by their threadbare clothes and their ill shod feet.

There was a lot in this city that was scary in the sense of personal misfortune. Everywhere the poor carved out a space to live, filling the cracks between legitimate buildings, erecting makeshift housing alongside train tracks and roadways or on the banks of the river and under cement overpasses. They also lived with us as servants, but then I thought of them as family. As long as they could live somewhere that seemed fair.

More disturbing were beggars sitting on the sidewalk, with misshapen legs, holding up hands with nothing, but nubs for fingers. My family ignored them. The misfortunes and fortunes of people were explained away with karma, the paying of a debt for crimes committed in another life. Karma or not, it made me uncomfortable to be on the other extreme. These maimed figures were, for me, a daily reminder of the disparities of life. They heightened my sense of reality.

Before the obligations of adulthood could erase this discomfort and replace it with the stress of having to fulfill my role as an income generating, social climbing, global market exploiting member of my family, I was plucked from the side of my pond and transplanted to the barren landscape of a California ranch house in the suburbs (with a pool).

When we moved to the United States, I did not realize why I felt so disoriented at what was being presented to me as the spectrum of reality, for I carried with me, like a phantom limb, the juxtaposition of the lives of the destitute with the lives of the wealthy. Here in the United States was a new world of elevated social justice where there was no homeless, no maimed, no street urchins selling flowers, no poor doing your chores for you. America pretty much had this equality thing down or so it seemed. (It is only when I see movies like Darwin's Nightmare or Tsotsi that I feel my reality is again affirmed.)

In 1968, the year of our arrival, my fifth grade teacher taught us that the civil rights movement meant that people of African heritage had a right to be treated equally though they once were slaves. (There were no black kids at the school, but I did know of Sidney Potier in Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, an important movie for my mother at the time). I accepted civil rights as a good thing. What a great country this was to be making amends for the past.

I was in junior high when the first Earth Day was launched and that too was a right and proper cause. I was eager to grow to adulthood in this increasingly progressive world of an enlightened people. Heh.

It would take me another decade or so to figure out how America was connected to Thailand. There were clues. When I saw teak salad bowls, from Thailand at Cost Plus, I thought it was a sign of rising economic status for my home country. When I learned from the environmental movement that 70% of the rainforest was cut down during the decade that I lived in Thailand, I realized those teak salad bowls were not so innocent a sign of progress. Environmentalists pointed out that the cutting of the rainforest meant drought (and floods). Drought meant poverty for farmers. Poverty meant girls were sold into the sex trade.

The environmental movement didn't quite make that last connection and the feminists who blamed Thailand (and by proxy me) for the sex trade didn't quite make that connection either. It was an American film critic in the underground press, who connected the dots for me, in a critique of a documentary about a Thai sex trade worker.

No I was not directly an advocate for the poor, but if the price of progress was the destruction of the rainforest and the lives of people who made their living from the land, what I was really advocating was that everyone else become more poor. I realize that I say this with the insouciance of one assured a lifetime of chocolate, but there is one more image from my childhood that holds an answer for me.

In the early hours of the morning there came down my street the monks in their saffron robes. Two of our maids would stand at the gate, with wrapped offerings of food, waiting for them. The solitary figure of a monk coming out of the morning mist evoked in me an otherworldly sacredness. They were barefoot and carried the black wooden bowl of their trade, for they too, were beggars. We took our shoes off, as they approached, out of our mutual respect for the teachings of the Buddha. Then we carefully placed our offerings in the black bowl.

Because they had voluntarily renounced the material life, in giving to them the food that they ate, a blessing was bestowed on us and on our household. A man who entered the monastery brought many blessings to his family and household and it was customary for young men and sometimes women to enter the monastery for three months.

Some time after I learned about the cutting down of the rainforests, monks became advocates of the forest, ordaining trees to protect them, counting on the respect of the population for the sacredness of the saffron cloth tied around the trees. That they had also brought attention to the sacredness of the trees themselves was right and fitting. At the same time young Americans were sitting in trees for extended periods of time trying to save them from the chainsaw too. Both the monks and the young Americans were being arrested for their advocacy of the forests. Neither has been stopped. Each bring blessings to their people and their community for the work they are doing. This is the movement I wanted to help grow, until all the world is filled with those who would renounce the material world (even if just for three months) to bring attention to the sacredness of the planet itself.

Also posted at energy bulletin