Return to the Bell Jar

The thought of my 30th high school reunion made me anxious as did all my returns to the institution that was the crucible of my coming of age, my coming out and my coming to terms with my undeveloped potential. This was no ordinary high school. This was Castilleja School for Girls, prep school to Stanford, hothouse for big brains, nursery for heirs to great fortunes and a secret garden where sensitive sorts found shelter from the abuses of the public school system.

It was a school that I clamored to go to though I did not yet know it existed. I was only a year in public school (after my arrival in California from Bangkok in 5th grade) when it became clear to me that I was not going to be able to relate to kids who were so amazingly clueless and rude about foreign countries. When the teachers told my mother I was weird because I spent all of recess reading, instead of playing with the other kids, that clinched it. The next year she enrolled me at a coed private elementary school, a "feeder school" to Castilleja.

My mother had gone to a girl's school in England and I had long romanced her experience - the picture of her wearing the school tie, her lifelong friendships, her stories of how she hated Latin and her love of Shakespeare. Both my parents treasured their education and had been top in their classes straight through to higher degrees. It was a lofty act to follow.

At 13 I wrote my application essay telling the school all the reasons I thought I would benefit from going there, coached by my mother who was in marketing at the time. The 45-minute entrance exam was but an appetizer of the exams to come and I was accepted with a partial scholarship. Outfitted with second hand uniforms and donated books, I took my place in the school at a time when girls' schools were still considered relics of a bygone era. It was the early 70's, who in their right mind would succumb to uniforms and a single sex education? Only snooty, uptight wealthy families sheltering their girls from drugs and boys or so it might seem.

But it was not wealth that defined us within those walls. The uniform equalized us and she who had to wear her camel hair coat over it and drive her late model sports car to school was considered to be indulging in bad taste. No, what did define us were our grades. I knew the approximate grade point average of every classmate, on a quarterly basis, as if I were watching stock prices. Those who made the honor roll had their names called in chapel and got to stand up. I ranked just above the middle. If I did not make honorable mention my ass was grass at home.

That I did not turn out to be phenomenally bright was a disappointment to me as well, but nor was I driven. I was doing what I needed to do to keep my head above water. Every day we were assigned 45 minutes of homework for each class and I usually carried five courses. Despite this crushing load I still hung out with friends all afternoon, made gifts for my love interests and wrote multiple pages in my journal about all the dramas that ensued.

If I could not be brilliant I could at least keep the company of those who were. Not the ones who had a well laid out plan to go to medical school or get a degree in engineering; they were not easily distracted. Those who were vulnerable to my charms were lost, living with their feelings close to the surface, their sexual orientation fluid, their identities up for grabs. They entertained me with a biting wit and wild creative imaginations expressed in their elaborate fiction writing. One friend took the final exam in English on LSD without any impact on her brainpower whatsoever; it simply amused her to do so.

Another declared that she was not going to write her term paper because I had become far too distracting (we were romantically involved, but too frightened to be lovers) and besides she couldn't make up her mind what her topic would be. In my eyes, this was nothing short of academic suicide and I would be damned if she was going to lay the blame on me. I picked her topic, presented her with the necessary books for research and refused to see her until she had done it. She teased me with it until the deadline.

"So why did you write it?" I asked her when she finally turned it in.

"Because the books were due and I didn't want you to have to pay a fine," she said. Thus I learned something about the coaching relationship.

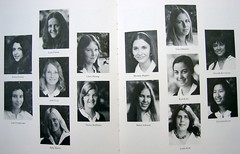

In my own way I was a star, too. I had a lead in the school play, was understudy to a prized role in the Christmas pageant, could do a handspring-back somersault, taught myself to juggle and ride a unicycle, had my stories published in the school magazine, wrote for the school paper and was editor of the yearbook. But as the years passed the demands on my intellect were not abated. I felt like I had a B grade brain and was a deviant on top of it due to my emerging sexual orientation.

I had excelled in English, then got bogged down later by demands on our analytic skills. What was the theme of Dostoyevsky's Crime and Punishment? This stumped me completely. What was a theme anyway? Years later I wondered if I was even culturally trained to recognize guilt; obligation yes, but not this all-consuming guilt. It just wasn't a Buddhist thing.

Nor did I get American history. What I had experienced of the United States was a military presence in South East Asia that pretty much implied that Americans went anywhere they wanted and did what they wanted. I did not see Americans as the underdog. The Boston tea party made little sense. Why would the 13 colonies want independence when they could just stick with the British Empire like the Canadians had done?

If it were not for an experimental class called Film Analysis, I would have believed my brain was as impenetrable as a lead bucket. I completely got The Graduate and his being in a fishbowl, constantly watched, despondent about his future prospects. The fish bowl theme showed up visually over and over and if it didn't you could pretend it did. That was the beauty of art criticism.

This bell jar of heated expectations under the watchful eye of teachers, who only had 15 students in a class, imprinted upon me a sense that I was always falling short. They pointed out my flashes of brilliance, then said I wasn't living up to my full potential. And what might that be, I wondered, for a good ten to twenty years afterwards.

What were we being groomed for - to carry on the old class culture, to be the CEOs of our own companies, to design pharmaceuticals for drug companies, to marry well and send our own girls back to the school for more of the same? Castilleja graduates had done all of these things, but nothing on the menu appealed to me. I felt obliged to go to college, but Castilleja had worn me out. I got my bachelors in graphic design so as not to have to read or write anything. I stayed a spectator with a perspective no one wanted. "Eco-feminist, lesbian peace activist", I wrote on the bottom of my nametag at my 10th reunion.

As reported in the alumni bulletin, my classmates continued to excel, earning one or more PhD's, husbands, children. How I longed to send in word of my accomplishments. I concentrated on forgetting Castilleja.

Then I learned that one could grow one's brain even into adulthood and I realized I was still caught in the expectations set by the school. "Hah", I thought, "now I'll catch up" and I set about to study my way into a bigger brain.

I read Buckminster Fuller who wrote that there was evidence the Bronze Age had its beginning in northeast Thailand, long before the cradle of civilization of my ancient history class. I read Howard Zinn's The People's History of America. Finally I understood American history. I read Maxine Hong Kingston and wrote my own history. I replaced patriarchal history altogether with Riane Eisler's The Chalice and The Blade.

For a long time I was mad at Castilleja for having been so Eurocentric. Then realized, that had it not been for the school forcing me to struggle through difficult material, I wouldn't have learned to read like this at all.

With my brain honed to shred and digest information like a shark patrolling the ocean, I finally felt ready to face my alma mater for my 30th reunion. Maybe, I hoped, my highly accomplished classmates had turned into matronly moms, their brains idling as they motored their kids around in the Land Rover. My neurotic friends, I knew, would not be there. They had long ago disappeared from the roster or had refused to return.

The evening alumni reception was hosted by the Head of the school in her Palo Alto home right behind the school. My classmates were already clustered in a circle, when I arrived, and I saw immediately that my hopes were dashed. They were every bit as poised, attractive and fit as, well, as I was. And they were dressed appropriately for a garden party in linen skirts, floral dresses and pastel pantsuits, whereas I had arrived on my kick scooter in my black jeans, a white shirt and a windbreaker printed with graphics. I had thrown on a stylin' tie just to show I was dressing up. They greeted me warmly nonetheless. Over dinner I would discover well-handled family lives and professional careers.

The Head herself was dressed in a business suit and looked like a CEO. She listened attentively to me recount my adventures with my environmental leadership program, but I had no idea how I was being perceived? Did the environment even register here in this school for excellence?

What I had seen of Castilleja at our 20th reunion was that it was even more intimidating and hard driving than when we were there. Once it was discovered that girls did better in single sex schools, the demand for places at Castilleja had taken off and the girls were handpicked. They were smarter, more articulate and talented than we had ever been. Castilleja could even lay claim to a champion Olympic gymnast. At the reception that evening, a 10th grader presented to us a classic violin solo played flawlessly. And when she finished she asked if she could play another. My jaw dropped open.

It was not until I attended the alumni program, on the campus the next day, that I got a sense of a school tuned to how girls learn. A young student spoke of the safe space her English teacher created in which to discuss sensitive topics. My English class had felt anything but safe, with Virginia Woolf crossing the boundaries of sexual identity all over the place and not one of us dared to mention it.

When the Head spoke about the future of Castilleja, she described how the school was going to open its curriculum up to a more global perspective. These girls, who were so smart that 65% of them graduated as National Merit Scholars, were going to be presented with the world. Right, I thought, more business opportunities for our best and brightest.

Then she gave a laundry list of issues she wanted them to learn about and solve - women's health, social justice, global warming, immigration and migration. I could hardly believe my ears. These were my own concerns past, present and future. They had already heard Al Gore speak about global warming at the school itself. She had seen his movie An Inconvenient Truth (not even released yet) and here she was calling on thirteen year old girls to solve the most pressing issues of our time. I got all choked up just listening to her.

She wanted to send them all to a developing country before they graduated and the school was offering trips to China and India, to any staff member who was interested, so that they could bring back a global perspective with which to open up the curriculum.

I already had something of a global perspective. I understood all of the issues she was talking about. I was, now, in alignment with the school that I had so struggled to impress. Suddenly, I felt the whole force of my education behind me, saying yes this is why you sharpened your brain so, your aim is true, your leadership is needed. Few had been able to light a fire under me before, but this felt like rocket fuel. Maybe I was going to fulfill my potential after all. Perhaps by my 40th reunion?