Truths My Father Told Me

The year I learned how to draw a peace symbol, I made one out of pipe cleaner and put it on our door as a party decoration in lieu of a Christmas wreath. My parents had fun parties full of liberal young people they knew from work. I was allowed to attend the parties and expected to make myself useful with the food and decorations. That year I opened the door to a man from my father's work at Stanford Research Institute (SRI).

"Isn't that a little hypocritical?" he said of the peace symbol, chuckling as he came through the door with his wife. It was 1972 and this was not my first clue that my father's business was the art of war, but it was the first time I understood that one was supposed to have an awareness of how such work impacted peace. I was in junior high at the time.

I asked my father about his work at my next opportunity alone with him. He was sitting in one of our swiveling, black vinyl chairs with the chrome legs. In his hand a globe shaped tumbler we got free from the gas station with every fill-up. I sat on the floor, Thai style with my feet tucked under, preferring to look up at him, respectfully, as I had been trained to do by my grandmother.

"Do you make bombs, Daddy?" I asked. I felt conspiratorial asking the question, ready for one of his wry answers like the one he offered when I asked him about the origin of Christmas when I was ten. Christmas, he told me, was invented by shopkeepers to get people to buy things.

"Don't tell her that," my mother had interrupted, offended even though she had rejected her Church of England upbringing. So she told me the story of Jesus Christ, which was nice, but kind of boring. I thought Christmas was all about Santa Claus, so my father's answer had more to offer. My mother wasn't within earshot for his answer about the bombs. With a slight smile, he said "No, I don't make bombs, I make the missiles that get them there."

I was somewhat relieved that I wouldn't have to say my daddy made bombs, but I also understood in that definition that lots of daddies were part of what I would come to learn was the defense industry and that this kind of work was a permanent part of modern life. We were, after all, in Silicon Valley, which before the wonders of the personal computer, had to work harder to cover this more ominous dark side. Now that I was in the know, I could learn to live with it as wryly as my father.

My mother upheld the humanitarian values in our house. She did not speak of my father's work, only told me that he had been to military school from the age of six. In our photo albums I looked at the pictures of my father in his Thai airforce uniform. He never saw combat. He used his engineering skills to help the Americans listen for troop movement on the Ho Chi Min Trail. I helped him test his equipment by walking our puppy up and down the lawn while he listened on his headphones.

That must have been about the time, he took a job in reconnaissance with SRI, which had a branch in Bangkok. This opened up the possibility of our immigrating to the US, which we did in 1968. Once here, my dad became a US citizen to be eligible for top-secret clearance. (My mother became a citizen, at the same time, to be eligible for government grants to work with disabled children, while I hung onto my British citizenship. Eventually I chose to become an American citizen to protect my right to free speech and to vote Reagan out of office.)

Shortly after we had settled in the US, my father took me to an open house at SRI in Menlo Park when I was 11 or so. They had a couple of chimpanzees in a cage playing with a football, but more exciting was the underwater rat maze. A scientist in his lab coat demonstrated this study with one of his star rats, while a group of us watched in breathless silence as the rat swam rapidly under the glass until he made it to the end and was fished out. The whole point of the exercise seemed to be to find out how quickly the rat would learn under pressure. Someone asked what happened if a rat didn't make it. The scientist smiled a half apologetic, but-I'm-just-doing-my-job smile, and said that they covered the tank until the rat could be taken out.

I did not question why this experiment had to be done in the first place, since this learning-under-pressure situation reflected the condition I knew as school. The man who asked the question was just not in the know—that death was inevitable and some were in the business of making it happen. (The key, I concluded, when I was old enough to make life choices, was not to get yourself in the maze in the first place, not to be obligated to anyone for your survival, not go into debt, not be forced to remain in the closet to keep a job. I wanted my freedom dammit.)

As protests against the Vietnam War heated up, students from Stanford University decided to stage a protest at SRI because of the defense work it was doing. My father was nervous that they would throw rocks or worse, but he came home laughing at the whole incident and described how the students were just sitting on the lawn and the building manager turned on the sprinklers, which got rid of most of them. Stanford University did drop its affiliation with SRI, which changed its name to SRI International. My father counted this as a victory, pleased that a band of peaceniks were not going to shut down his place of work and now they even had the prestige of being a global corporation.

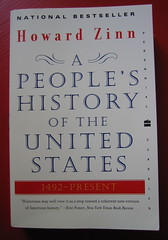

Meanwhile, I had caught a glimpse of the peace movement, which I would later join having heard enough of how the long term consequences of the Vietnam war had impacted the people of South East Asia, from land mine victims, to the growth of the sex trade in Bangkok to accommodate American soldiers on leave, to the affects of agent Orange on those exposed, to the killing fields of Cambodia. And then to find out, when I read "A People's History of the United States", that the war didn't even have to happen because the whole Gulf of Tonkin incident was a lie.

Where I could not get past the wrenching empathy I had for the Vietnamese and Cambodian people (who were being portrayed in movies by Thai people so looked even more like family), my father was able to see everyone as a potential enemy even family. My mother left him as soon as I was out of the house. He managed to snare two more wives, but he had only one friend to his name, a proud father of a marine.

On the eve of the Persian Gulf war, he found it amusing that I was marching in peace marches, so sure was he that he would be on the winning side—the side that got to go to war. While I, righteous as I was with the total wrongness of it, would be on the losing side, the side of the peace movement. I was puzzled because I was clearly winning the moral argument, but he didn't seem to care at all about the bombing of citizens and the destruction of a country.

Then he let slip that he had a project he wanted to test which would bring him recognition at work. This was the heads-up display he was working on for Kaiser Aeronautics. As my father described it, this display would be used in helmets to allow pilots to fly and shoot without having to look down at the instrument panel. He was hoping he would get to go to Iraq to see it in use by helicopter pilots. This, I realized, was a man who loved his work. He did get his war and the accolades that went with it including a US patent for his work on the display.

It was true, he had never given much credence for the reasons that were given to go to war, not even the good war. He did tell me that US intelligence had known about the coming attack on Pearl Harbor and that it was allowed to happen to convince the American people of the necessity for a response. The day of the 9/11 "attacks", I asked him what he thought would happen. "We bomb Afghanistan", he replied without a second thought.

His truth spared me the stories of national security and the terrorist threat that were on the lips of our leaders. My father lived in a world that assumed constant war making. War was how nations got the resources it wanted, his outlook implied. (Tin and rubber it had been in South East Asia not communism.) It was just that not many were admitting it quite like my father did. What chance did peace have against a whole industry of people excited by destruction and the desire to win to the point of annihilation, not to mention the arm-everybody consequences of the arms trade?

I spoke no more of peace to him, only shared news about the family in Thailand. Often he would ask me to proofread a letter he had written to one business or another complaining about a product malfunction or customer service error. When his second wife left him he sent me to the deposition with the lawyers to make sure she wasn't going to cheat him. (I never let on to her my purpose for that appearance.) I also found myself mediating for him when his live-in maid from Thailand refused to speak to him. We did share some common ground in our interest in tools and he was able to help me fix things, but when he suffered a recurrence of his throat cancer (attributed to smoking), I was secretly relieved that he might not be around much longer; that I would actually be able to live the second half of my life without having to bridge his nihilistic perspective.

The final truth that my father revealed was that his battle-ready stance would not help him in his fight against cancer. He had been a fit man and the doctors were confident that he would live several more years once he got past the surgery, even though the cancer was not eradicated. He wouldn't fight at all, but lay defeated, wishing to die; refusing to do anything the doctors told him to do to aid in his recovery. We who cared for him thought that he might gain strength if he adopted his usual strategy of plotting revenge. We urged him to recover so he could sue his doctor. (He did fault the original radiation treatment for causing the recurrence that produced a tumor in his neck.) But revenge didn't interest him if he still had cancer. For him the battle was already lost. He had nothing to fight for. In the end he died (in 2002) of pneumonia, the default death.

I was free, then, to study war no more, but I had acquired a taste for it. The US launched its invasion of Iraq, spinning lies I wasn't about to believe. As it dragged on, I wanted to know what was really motivating our administration, how far they would go to control the Middle East and if peace was even relevant in the face of empire building.

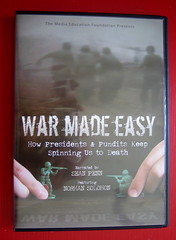

"I'll just settle for knowing the truth before I die," I told a peace activist at a recent lecture by Norman Solomon, author of the book "War Made Easy", now a critically acclaimed film. And does the truth set you free? No it just makes you feel like you're part of the in-the-know crowd. Is the peace movement dead? Not if you consider that the US has not dropped another nuke since Nagasaki for fear of the response of the American people. Will we end the illegal occupation of Iraq? (It's illegal for an occupying nation to change the existing laws of a country being occupied.) Only when multi-national (American) corporations have made every last deal there is to make in the privatization of Iraq's nationalized industries (not just oil). Same as happened in Yugoslavia.

Check out these movies for more on the business of war-making:

War Made Easy: How Presidents and Pundits Keep Spinning Us to Death: Documentary about the use of propaganda by our leaders and the media to persuade us that war is the only answer. Now playing in theatres. Or you can borrow the DVD from me.

No End In Sight: This recent film is considered to be the definitive documentary of the war in Iraq. One of the clearest, non-political explanations of what went wrong and who is responsible.

Fog of War: Eleven Lessons From The Life of Robert S. McNamara. An Oscar winning documentary interviewing Robert McNamara regarding the decisions made in the war in Vietnam. A telling film about how our best and brightest justify war.

Lord of War: An arms trader, who is also a father, contemplates the morality of his work in this wry drama starring Nicolas Cage. Serves as an uncanny reflection of our attitude as a nation that has become the world's largest arms exporter. Arms manufacturing is one of our nations largest industries.

Labels: defense industry, family, peace movement, war