Nothing Space

Some colleagues and I were chatting about what radio stations we listened to in the car. We drive quite a bit as traveling consultants so this was a major part of our lives. When it came to my turn I told them I didn't listen to anything. They looked at me blankly.

"I just get in the car and drive," I explained. No one asked why and the conversation ended abruptly just when it was getting interesting. Listening to nothing is one of my secret weapons.

At first, I didn't turn on my radio for the first few miles because I was listening to the car. I had read, in a book on car care, that this was the way to keep tabs on the health of the car, to hear any new rattle or grinding that might indicate something in need of repair. Then my thoughts would take over and I would forget to turn on the radio for longer and longer periods of time. Eventually I got to appreciate the spaciousness of having my mind to myself, uninterrupted by urgent radio announcers.

I'd had a similar conversation with another colleague who had come to help me with a construction project in my mother's garage. She asked if I listened to the radio while I worked on this project. Again when I said no, it was a conversation stopper.

I began to wonder why this was so unusual not to listen to anything. After all, people have unplugged their TVs or refused to have one; why was it so unusual to do without an audio form of entertainment? I was already reading 13 magazine subscriptions, 9 newsletters, 7 Yahoo groups and a daily paper, while my partner surfs the TV news every night and sends me online CNN bulletins of items of interest.

We now have the technology for multiple levels of input everywhere at any time. We are expected to access so many forms of information that listening to the radio or an iPod is one of the more pleasant, relaxing ones. Not to listen while doing something mundane like cleaning or driving seems odd. And in this era of multi-tasking you would be guilty of wasting your time.

What available space we have left is being consumed to feed the need to stay connected and informed. A client working at Cisco told me how it is now customary for employees to answer their e-mail, on their laptop, while they attend meetings. They end up agreeing to do things without fully realizing what it is they have committed to. We now know, from a recent survey, that multi-tasking makes us dumber. The few seconds it takes to switch from one task to another diminishes our IQ and fragments the brain.

E-mail has taken up so much of our available time that organizer and time management coach, Julie Morgenstern, counsels her clients not to read e-mail first thing in the morning, but to do the most important thing on their to-do list first. I told this to a client recently and an astonished look crossed her face. Not answer e-mail, but that's the most exciting part of my day. (It's true it does keep one from feeling isolated especially when working from home. And sometimes I do advise depressed clients to read their e-mail as an incentive to start the day.)

We are so pressed to take in and respond to data and messages that it is as if we are continually trying to breath in more air, without exhaling. Or perhaps we are hyperventilating in the effort to take in information and send it out again.

We already know about the stress of information overload. The prescribed treatment? Anti-depressants or tranquilizers. Another syndrome to keep the pharmaceuticals going. Why not just stop already? We may just be constipated - our system clogged with input. And then to relax, we layer on more input, packing it down tight.

I have to keep reminding clients that they can't possibly read everything they have put in their to-read piles. I have joked that I was going to start an adjunct business reading other peoples' to-read pile and telling them if there was anything they needed to know.

Recently, I learned that the average time people take to think about anything is three minutes. It makes me wonder what, then, are they doing with all that input?

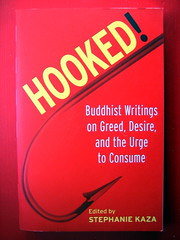

Three minutes is just about right for a consumer society. It's enough time to decide to make a purchase, froogle it and buy it, without thinking about the long-term impact of owning the object, maintaining it, then disposing of it. Not to mention, the external costs to the environment and to the people making the item. The volume of transactions in well-to-do households have created a niche for organizers specializing in Quicken and Quick Books. (I still record my transactions by hand, the better to take in the full impact of my purchasing decisions.) I've often thought that volume is a large part of what keeps organizers in business. Too much input of stuff on top of all the information to keep up with.

When I first heard the term "information age" I feared that I was simply not up to it. I hadn't mastered channel surfing. Just the words "information age" made me feel inadequate. The phrase signaled that information was now a commodity. If you had it you were marketable, you were on top of things. Savvy consultants became vendors of specialized knowledge, selling exactly the information people needed to cut through the overwhelm. Common sense itself was marketable in this glut of information.

For we had entered the age of fast food information. And we were supersizing it. It was time to read the ingredients on the side of the package: hype, sensationalism, fear based propaganda, PR packaged as news, eye candy, urban legends, consumer brainwashing, product information, celebrity drama, revisionist history, disinformation and just plain old misinformation. Much of the reading I was doing was an attempt to get to the bottom of it. To make sense of things.

Listening to nothing while driving is a good time to digest. It's a chance for me to allow my thoughts to flow continuously, clear out junk information, dispel fears, narrate stories and settle into calm and clarity. My thoughts are the connecting fluid of my mind, the river that runs through it. If I didn't have this nothing space, my mind would start skipping, forgetting more than I do already or fall apart altogether. Nothing space is a chance for my mind to exhale.

Some might call this taking time to reflect, but that is too goal oriented for me. Reflect on what? I prefer to think of nothing space as an informal version of meditation; the mudroom of the mind where one takes off one's shoes to leave behind the dirt picked up from outdoors. The mudroom as a place of transition.

Driving alone lends itself to these thought journeys. So does refinishing furniture, cleaning, ironing or folding laundry. I would let my thoughts run unleashed like a pet running around the house, the task at hand serving as a grounding rod, bringing me back to mindfulness. An hour or two of this flow and my mind is far calmer than when I began. I am better at listening, not only to people, but to my surroundings. Inanimate objects would offer up their secrets.

In letting loose my thoughts, I was aspiring to journey to a new landscape and the possibility of transformation. The journey might take years. As when I would ask myself questions left over from my schooling. Was it true, for instance, that if we do not study history we are bound to repeat it? Or was the problem more that we keep telling ourselves the same violent, war-loving tales of conquest and triumph? Is the collapse of civilization inevitable given ecological limits and the propensity of humans for unsustainable growth? If so, maybe the Old Testament was a human centric (patriarchal) telling of a previous collapse and the need to rebuild. "May your descendants number in the ten thousands."

I could follow lengthy trails of thought journeys, then pause to gather information in order to answer the questions that came up. Information of my own choosing, not the bombardment of information from every portal. Silence (or rather listening to ambient noise) while doing, happens to be my refuge. Others might find their nothing space in an uncluttered room or outdoors in nature (which happens infrequently. Americans spend 90% of their day indoors and choose to extend that artificial environment to their cars by turning on the radio.)

When I listen to the radio, be it music, Terry Gross or news reports, the input reverberates in my mind long after I hear it, interrupting my interior space. Allowing my own thoughts to be the dominant voice in my head allows me to be the sole commentator, the narrator of my life. My mind feels less fragmented and the activities of my day become a more cohesive whole.

Nothing happening may be the invisible un-glue, the space that keeps everything from becoming one big overwhelming ball of everything.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home