Cultural Whiplash In Bangkok

"What about a book about earthen houses," I tentatively suggested to Raja and his wife, Nor, the managing director of Blue Toffee, the publishing house that is producing my book "Diamonds in My Pocket." We are in Raja's car which was actually a great place for a meeting, since he had a driver and we could fully concentrate on our conversation within the confines of the leather upholstery and cool filtered air of the sealed Beemer, despite being in the middle of rush hour traffic.

"Lot's of books in the States are about natural buildings," I explain thinking of glossy coffee table books full of photographs of strawbale cottages shot at sunrise, "they are very beautiful and people like to buy these books. Though not the same people who buy diamonds," I add turning to Nor. "That all right," she says in her characteristic short cut English with flat Thai accent, "different niche." Nor is in the middle of producing her third book in a series of books on gems; this one is a guide to picking out diamonds.

Yes, different niche, indeed; that's why my diamonds are in my pocket. The title of my book made Nor gasp when she first heard it. "Why in your pocket?" she had asked. I had been at a loss to explain. I was pleased that she got it now. I had been quite apprehensive about the status of my relationship with my cousin, Nor, before coming to Bangkok and was relieved to find that my somewhat harsh characterization of her, depicting her as a materialist conscious of every nuance of status, in my memoir, had not given her reason to distance me. On the contrary, as soon as I arrived at the newly refurbished condo turned office of this publishing enterprise that Raja had created following his retirement, I immediately felt welcomed into the Blue Toffee family as one of its authors; the talent as they say in the performing arts.

The sight of my book on display in Raja's office next to the three others that were currently on the Blue Toffee play list, gave me a feeling of stardom that I was not quite ready to grasp. There it was, a real book with my mother and three year old me looking out from the cover. It actually did make me want to pick it up and flip through it. Who was this fahrang woman with the Thai child? This would be a different book from the usual English language books about Thai prostitutes and the Western men ensnared by them or alternatively the truly unlucky who find themselves in a Thai prison, Midnight Express style, following a drug bust. Not since the 60s, it seemed, had anyone penned a book in English of normal life in Thailand (if anything can be said to be normal in this country of extreme contrasts).

In fact women writers, even from the Western hemisphere, were hard to find in this land that had inspired Conrad and Maugham and a handful of other Westerners who were well known enough to have suites named after them at the historical world class Oriental Hotel. I did find them though, on the internet, four years ago under the name Bangkok Women's Writers Group, listed under events in the Sukhumvit area, the trendy, up scale, ex pat district that happened to be where my family had a house. It was to a meeting with this group that I was going and Nor and Raja had offered to drop me off.

The group had just come out with an anthology called Bangkok Blondes of their collected writing. It was well received so far and had won some award for South East Asia. I wanted to show them a copy of my book (a mockup, the actual book was still in the queue waiting at the printshop, in Singapore) and probe them for tips on promoting the book. Serendipitously, they were meeting during the five days I was in Bangkok, at seven that night at a coffee shop nearby. Traffic had come to a standstill. I was only a few blocks away.

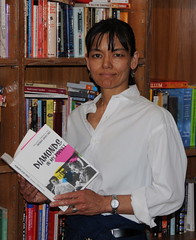

"It's seven already. I can get there faster if I walk," I announced to Nor and Raja. We had been in traffic for fourty minutes and had traveled about two miles. They agreed, though only fahrung (Westerners) actually get out and walk. That was okay with me. I was a fahrung with a niche. Under the Blue Toffee "lifestyle" brand I would be the sustainability expert. I was all over this niche, envisioning a new wardrobe of outfits. I was already wearing the classic farmer's pants made from ikat textiles. I had hemmed them shorter to a stylish knee length. My tailored white shirt with French cuffs, closed with my father's cuff links and accessorized with silver jewelry, made me presentable to Nor's stylist eye.

I opened the car door, nearly nailing a motorcyclist, then hastily pulled it closed again and looked behind to see a whole stream of motorcyclists with passengers streaming up the column of stopped traffic. Then one was merciful, seeing I was still trying to exit; he stopped and waited as I hopped out. I nodded my thanks to him, waving good-bye to Nor and Raja.

Cultural Whiplash In The Country

This entire trip was one of cultural whiplash I had not quite breached before and if I thought about it too much my head would explode. I had just spent two weeks in the flat, dry landscape of Isaan, in north eastern Thailand on a tour of sustainable projects that I had not known existed before my foray into the world of natural building. Searching for a workshop in cob building on the internet, four years ago, I had found Pun Pun farms near Chiengmai in Northern Thailand, but had not been able to join any of their building events. Still, because this group was in Thailand, I was very interested in their efforts and had kept an eye on them until I was finally able to come on this tour—their first road trip. Even so, I knew that breaking away from my family's Bangkok mindset would not be easy especially if they knew I was traveling alone.

"Driving at night is a no no," warned my friend G-up regarding my trip to Yasathorn, the meet-up point for the tour. (I had wanted G-up to come with me because of her interest in the environment, but she was held up at work.) To hear a city person talk of the country you would think that there were bands of robbers waiting by the side of the road with machetes to ambush busloads of tourists and wealthy Thais in sedans. I remembered a cautionary tale that had been told to me by my family when I was twenty. It involved a girl who wanted to join her friends at the beach at Pattaya, but her parents had said no; she took a taxi alone and ended up raped and dead.

In 1990 I traveled to the outback of Brazil with three other women. City people living in San Paulo warned us that there was nothing out in the Sertao, but snakes and bandits; they themselves had never been to that region. How curious, this psychological barrier between the modernized, educated citizens of urban third world cities and their poor country counterparts. Turned out that the sweetest people lived out in the Brazilian scrubland, visited only rarely by priests, and in one village an American woman who had stayed for two years, learned Portuguese from scratch and painted murals all over the room they had offered to her. "She was like a daughter of the town," the villagers mused nostalgically as they showed us her room.

To cross this barrier between first world city and third world country and to appease my anxious relatives, I would need protective camouflage. I summoned an American of my own, via group e-mail to those going on the tour. She arrived at my family compound, after dark, having traveled by bus from an ashram, a couple hours outside of Bangkok. She had neglected to bring the address and directions I had given her, but was eventually able to reach me by phone having gotten lost on the Sky Train.

As soon as she laid down her large framed, back pack on the teak parquet floor of my father's house and adjusted her waist length brown pony tail, I recognized her for the intrepid footloose youth that span the globe, post-college or between years. Irena was her name. Yes, she would do nicely. Cash strapped backpackers were not generally a target of roadside hijackings.

Early in the morning, my aunt's driver drove us in the family minivan to the bus station and bid us farewell. Ten hours later by air conditioned bus that had stopped at every podunk town, we arrived after dark in Yasathorn, having missed the pickup time of our tour by a couple of hours. We called and were instructed to find a taxi and make our way out to the farm. I did not tell Irena that two women out in the country at night was a "no no," although I was beginning to worry. I would just have to hang with her fearless American reality. I was, after all, armed with a black belt.

A motorcycle driver for hire, seeing that we had just got off the bus approached us. Realizing how far we wanted to go, he summoned for us another driver who had a pickup truck. This chap's scraggly beard and homeboy hat did not comfort me, but we got in nevertheless and headed out to our destination fourty minutes away, with me jammed up against the stick shift. There was no address. The driver seemed as nervous as me. We would just have to ask our way there or rather he wanted me to ask, to give validity to his being there—a strange man with a truck. At the first house where people were still out in the yard, I got out and described to them, with my ten year old Thai, the farmer who had a fahrung wife whose farm we were seeking. Ah yes, said the man, the place of the "Baan Din"—the earthen houses. This was promising, but still we did not find it and stopped at a hardware store where the owner kindly jumped on his scooter and bid us follow him. He led us to another house high up on stilts with a small yard.

"This isn't how I pictured it at all," said Irena when we pulled up, but we were not there yet. A woman came out for a discussion with the driver. I was not following the conversation and thought we were lost. Could we call them? I asked the driver who repeated my request to the family. A pause as the woman took out her cell phone. This comforting device in the middle of what still looked like pre-industrial Thailand made me want to laugh. She dialed a number and handed it to me. I spoke into it in English. A man's voice with a slight Thai accent gently told me in English, that we need only follow this woman's son and he would lead us there on his scooter.

When I saw the first distinctly un-Thai earthen house and a group with a blond person in it, milling about under fluorescent lighting, I knew we were there, wherever there might be. I had done it. I had escaped the pod lifestyle of Bangkok as it was lived from air-conditioned car to indoor shopping mall to air-conditioned condo. And this, I could be sure, was no ordinary tourist expedition with pre-planned elephant trek ending at a photo-op waterfall. This was a field study into the lives of real people not making a living from the tourist trade, a land that had once been teak forests, and was home to so many women currently in the sex trade. This was the story of a land in recovery from the Western selling of the Green Revolution of chemical agribusiness fame, followed by the economic roller coaster of globalization. Now it would be my story to tell too.

Labels: Bangkok, publishing, Thailand, travel, up-country

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home