The Hope of Innovation

Supposedly one of the reasons that the world tolerates Americans, and indeed one of the reasons we tolerate ourselves, is because we have a reputation for innovation. As an innovator myself I can vouch for this.

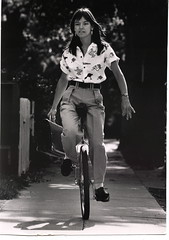

When I learned how to ride a unicycle in high school, I was assisted by a number of factors. First I was introduced to the idea while attending the Fourth of July parade in Redwood City (affectionately known as The Redneck City Parade) where I saw a drill team from Concord riding unicycles. That ordinary Americans were doing something unusual in an ordinary way made it entirely possible for me to think to do such a thing. I went to my local library and found a book devoted to unicycle riding. I was able to buy one locally at a bike shop (made by Schwin). Over a holiday weekend I mastered the thing and was much admired when I showed off my new skill at school. The following year I took it to college where it became my mode of transportation (and later elevated to my 15 minutes of fame, on the evening news, as a Green commuter).

That summer I went to Thailand and suggested to my relatives that the unicycle would be a terrific way for me to get around Bangkok. They were horrified and forbid me to think of doing such a thing.

"People will get into a car wreck trying to look at you," said one aunt, the only one who actually walked anywhere. The underlying message was that a person of my class, representing the family name as we all did, was not to perform acts of freakishness in public. There were rules about what was seemly. My grandmother, in particular, laid down the law guided by what was being done by her betters. Or not done.

In the current economic collapse scenario, innovation is again the hope that pundits are calling upon to save us rather than accept any form of downward mobility. That such downward mobility might lead to self-sufficiency is not mentioned.

I noted at an early age that my grandmother was unable to do anything for herself, though she could artfully arrange dried flowers and wrap gifts with precision. She was always calling for the maids to help her. I never saw her cook; I'm not sure she ever learned to ride a bicycle or to swim, but she had played a championship game of tennis in her youth and was an expert at ordering people about including me.

I vowed that I would not meet the same fate. I would not let wealth render me forever dependent on the skills of others. How would one travel or go on adventures like the children in my much-loved English books who spent their summers sailing?

"If not duffers won't drown," their father had said.

Most of my aunts could not swim. My relatives were of a class that had not learned to swim because only the poor, who were forced to live on the river, did so. (My British mother made sure I had swimming lessons when we joined the Sports Club.)

I loved the water. In the context of my family, I was forever aspiring to be downwardly mobile.

Poor As Four Letter Word

Few cultures aspire to be downwardly mobile. Poor is a category cloaked in shame, especially in America. Once when a roommate complained that she didn't have enough money to take a European vacation and thus wouldn't be able to go on vacation at all, I thought I was being helpful when I said, "Well there's always camping." This, to me, was a fun holiday that allowed practice of many skills of independence, in places of natural beauty, surrounded by others of like mind.

My suggestion was met with a look of horror and she walked out of the room as if I had delivered an ethnic slur. She had perceived me to be a person of wealth telling the lesser endowed how to live in a manner they could afford. This was, I realized, the height of rudeness in a land where everyone had the right to aspire to be upwardly mobile. Was the reluctance to identify as poor(er) an Achilles heel of American culture? How very Grey Gardens of us.

I learned to reframe my pursuits. Americans still valued self-sufficiency, religious practices were respected and even more so political ones; eccentricity fit right in with the cult of the individual, artistic interpretations are admired and experimentation and innovation are highly prized. As long as I didn't mention that I was also trying to be frugal, I could do whatever fun thing I wanted to do and inspire others with my stylish, politically correct, eco-sustainable example.

Skills Lost

Still, I couldn't help noticing that my peers were going the way of my grandmother. In the upward mobility and general wealth of American culture, skills of self-sufficiency had been lost over the last three decades.

I asked a number of women friends whether they could sew. Those, at least five years older than me, were almost all able to sew, but didn't anymore because clothes were so cheap to buy (imported from all the sweatshops in Asia). They were right. There was very little economic reward in sewing anymore. The only reason I sewed at all was to learn ethnic patterns and come up with my own designs. Thus the urge to design was a key to the motivation to innovate.

In college, I had come across a book called "Design Yourself". It was full of energetic cartoons of the empowering, "you can do it" kind. I loved the idea of going through life as a designer, choosing what came into my life and being encouraged to restyle it. In my home country fashion was a marker of class position so it was safest to copy and later buy already established designer clothing and accessories from the West. The same for cars, electronics and home furnishings.

The book "Design Yourself" was the text for a theater arts class on set design. Theater arts had been, for me, a microcosm of useful skills. It was while building sets at the Children's Theater that I first learned to use a hammer in 6th grade. And it was in the costume department that I learned about historical dress which in turn allowed me to innovate a unique style of my own.

As part of the stage crew, I learned how to manage ropes and pulleys, handle antique props and move things around in the dark. None of this was happening when I performed in school plays in Bangkok. There were dressmakers, stage crews and labor all from another class to take care of everything and no public library in which to research in the theater arts section.

High Tech vs. Physical Reality

As the arts give way to all things computer (funding for the arts cut from schools and all) there are fewer venues for using hand tools and devising mechanical things. My father, an electrical and mechanical engineer, fearing that he would be made obsolete by the advent of the computer, decided to build one at home so he could learn how it worked. It took him close to a year working every evening with a soldering iron. This was not a skill I was drawn to. When I did learn the computer I was, like most of the pre-computer generation, frustrated by the logic and precision demanded. It was not until icons representing reality, i.e.: a trash can, were added that computers were made "user friendly". Thus translated into human terms through symbols, we became computer literate, while a new generation was submerged in a "virtual reality".

I have been assured by academic studies that computers have not impaired the ability of the human brain to solve problems. But I fear that it has impaired the ability to struggle with the world of physical things.

My suspicions were confirmed by a biography I read of a man, my age, who had taught himself frontier skills as a teen and later started a school. He observed that the children who attended his camp lacked basic understanding of the physical laws of nature—leverage, inertia, momentum and thermodynamics. They would, for instance, attempt to walk with a bucket of water at arms length, in front of them. They had never played with simple toys, thus had no idea that a hoop could be made to spin along the road like a wheel. Their lives no longer offered these lessons.

A friend teaching at a university told me she had been a drawing teacher over a long enough time span, now, to note the deterioration in hand skills due largely to students spending less and less time on a single drawing. My friend took to assigning "time" homework to her students so they would give the time necessary to hone their drawing skills. This confirmed for me that people were not spending as much time doing things.

While women no longer sewed, men no longer fixed things. It was cheaper to buy new, again due to the global economic efficiency of far-flung sweatshops. Having attempted to fix many a discarded appliance, myself, I too, found that it wasn't worth it. Either you couldn't get the parts or the item broken was plastic and disfigured beyond repair. Then there was the circuit board. I once had an oven repaired in a rental unit I managed. I was flabbergasted to learn that it was broken because cockroaches had eaten away the circuit board and disabled the on/off function. Civilization brought down by the appetite of cockroaches! Circuit board as weak link of modern infrastructure! Circuit boards do not lend themselves to home repair. It was replaced by another from that far-flung sweatshop.

Without practice observing mechanical things, it gets harder to see how stuff works and think to struggle with something to learn how it might be made to work again. People with a high tolerance for such struggle make good plumbers and auto mechanics.

How We Learn

Commentators like to point out that diversity is the key to our strength, implying that there will always be Americans with the right skill set to solve problems as if the US were a slot machine prompted by a pull of the lever to come up with a new set of winning symbols. The actual benefit of this diversity is in the cross-pollination that is possible through people and access to information. American social boundaries are more permeable, our hierarchy more accessible. Anyone who can write a simple proposal and profess knowledge of any subject of possible interest (but not bomb making, of course) can apply to teach a class at a community college where they are immediately perceived as an "expert" in their field.

Thus our diminishing patience and skill set may be offset by our willingness to learn new things, for Americans are willing to learn from those not of their class. (But if from someone who is poor, it will probably be a monastic teaching Buddhist meditation.)

In the 70s I found a paperback at the library called "Living Poor With Style" by Earnest Callenbach. It was filled with attitude about how curtailing your need for money would allow you to be free to do more of what you wanted to do. I took this message to heart. The book went out of print, resurfacing two decades later with a different title that replaced the word "poor" with "cheaply". It was hardly worth reading having been shorn of attitude. (But you can get the original; a used copy on Amazon priced at close to a hundred dollars.)

In those intervening years, technology, particularly high tech Western technology has been telling people how to live expensively the world over. After the economic collapse in Thailand in 1998, the poor discovered that there are worse things than being poor and that is being in debt. A movement of peasant farmers quietly began to reclaim the low tech indigenous folk innovations of the peasant people and also of learned people who had perfected sustainable practices.

I was encouraged that such skills are not lost, but I have come to believe that once a culture is invested in high levels of centralized technology it will use every last breath to save that unsustainable infrastructure before turning to alternatives. There simply is too much at stake in terms of jobs, profit and stability. It looks like collapse will have to be our saving grace.

I found clues to such a future in the story of the Pueblo people, the ancient Native American culture admired for their advanced society and building techniques. They were said to have disappeared, leaving no descendants, starved out by drought causing the collapse of their food supply. On closer inspection scholars observed that they may have migrated or possibly their descendants became the plains Indians who populated the land following their demise.

The name for this ancient people is Anasazi, which is Navajo for "enemy ancestor". I was chilled by the implications of this phrase. To speak of an advanced culture, that preceded you, in such language implied that it was understood how such a lifestyle was also their folly. At the same time, I was heartened that at least they had learned and developed a culture of sustainable practices. If we are the enemy ancestors of a future people, this was a hope that our descendants will find their way regardless.

Labels: collapse, environment, innovation, sustainability