Prop 8: The Hate That Ate California

For my last post of the year, I debrief one of the more contentious battles of 2008—gay marriage and Proposition 8. And not over yet, by half. After seeing the film Milk, which covered a lot of the same geography and time period as I lived, I was inspired to revisit my own LGBT history in search of a personal perspective on how we got here. The sentiment "may you live in interesting times" has more than ever characterized this last year. A curse or opportunity for change?

Best wishes to all for 2009.

The Closet

In high school I read The Diary of Anne Frank—twice. It was not an assigned book at any time at my all girl's school. For our civil rights education we were assigned Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man. I didn't understand what Ellison was on about because I didn't get why being invisible was bad. I read Anne Frank because she kept a diary as I did; I was the same age as she was when she wrote her first entry. I read it again in my senior year because by that time I well understood what it meant to be persecuted; to be forced to hide your self for fear of dire consequences.

After Yes On 8 passed, a black woman on the radio said that calling gay rights a civil rights issue was a slight to the black civil rights movement because black people had been killed for the color of their skin and that wasn't the case for gay people. To that sentiment I pose the question "What were your parents reaction when you told them you were black?"

The Closet is an insidious form of persecution hidden as it is within a medical model of mental illness or worse, spiritual damnation while seeming to offer a choice. I was 15 when I came to terms with it. To be cherry picked for persecution, solo like this, at so young an age, leaves scars. The line between self-hatred and liberation, a war zone littered with barbed comments and conversational landmines through which I could only scurry for cover. I was lucky that my religious background did not also damn me. The Thais believed I was paying a karmic debt from a previous life, nothing serious. In the US I knew my choices—stay hidden or risk social ostracism and likely economic exclusion. Only later would I understand that this "don't ask, don't tell" policy qualified as political oppression.

The payoff of coming early to such self knowledge was a heightening of emotion that was so focused it took you to the edge of a precipice with the excitement of it. Two others were drawn to my erotic awakening—classmates at my school. We exchanged notes—cryptic prose and Rumi poems—folded into tiny packages, handed off discreetly in class. Hidden corners of campus revealed their erotic potential as meeting places where we could exchange searching looks and a single whispered feeling. Rare sleepovers were tense with anticipation of a possible caress, always in danger of being discovered, the space between us a treacherous crossing.

The Jewish one shared her love with joy; the daughter of the Christian fundamentalist tormented me with her refusal to be the queer. It was I who was sick, she implied and told me I would not survive in the real world, not the way I was, so obviously butch like this.

Recently, while channel surfing, I caught a few minutes of a wildlife show on tigers in captivity being released into the wild. For the tiger in question it was too late for he passed his days in the wild pacing out a piece of ground the dimensions of the cage he had originally occupied in the zoo. There, I thought, is a thing of beauty that has been too long in the closet.

The Personal Is Political

I was surprised to learn later that very few lesbians of my era came out in high school, oblivious of their alien feelings until someone brought them out in college or much later after husbands and children. How could they miss something like that? I felt more affinity with gay men. My sexual tastes too, traced the erotic arc of men meeting anonymously in public places, exchanging looks, a furtive whisper, the urgency and pleasures of prominent boy parts I imagined onto my own. What was penis envy, exactly, when the power of the mind made this so accessible? I eroticized the black leather, the military uniforms, the power plays of top and bottom, the glamour of drag queens.

While San Francisco was galvanizing the gay movement by electing Harvey Milk, our first openly gay politician, a celebrity Christian was busy persecuting us with an open hatred of the act of gay sex. The public and the media did not speak out in our defense. We would duke it out on our own with the help of an underground of left leaning progressives, boycotting Florida orange juice. It worked. Anita Bryant's career was in the toilet, gay power was born (again), but the hatred was not doused.

The lesbian community was deeply immersed in the ideology of feminism. I was too much of a style queen to settle for such rigid political correctness. Where was the glamour of it? Sex was hardly mentioned. That was the realm of the men and their numbers game racking up sexual encounters. Gay men and lesbians stayed largely separate. "Fishboats" a man called me and my bisexual girlfriend, as we walked down the Castro. How culinary and picturesque.

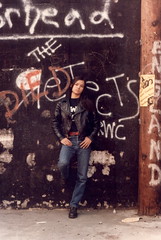

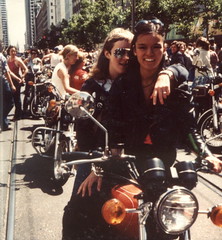

I wove into my persona a black leather jacket, zip up the side leather pants, black steel toe construction boots and a motorcycle and rode with the Dykes on Bikes in the parade in 1981. The first year we rode, the organizers put us at the middle of the parade instead of the front. It was an attempt to tone down the event of the pervert aspects of the gay community in the hopes of becoming more acceptable. This included drag queens, us and that naked guy wearing the boa constrictor. Nevertheless, I was ecstatic to be so out in the open cheered like a returning hero in a ticker-tape parade.

The following year we were back at the head of the parade. The notion of acceptability having been found hollow. Who were we fooling? And what of the hypocrisy of restricting our own people of the diversity of sexual expression? There was, I believed, a power in sexual energy; why else would it be taboo, unfairly suppressed by an authoritarian culture pouring cement over the expression of the divine life force. Somehow it would break through like a weed in sidewalk paving.

Soon after that we were wearing black ribbons to mark the appearance of AIDS. The hostility between the gay and lesbian community fell to the wayside. Ideology gave way to caretaking. Women gained ground in political status and leadership positions, while the men adopted healing practices and taught safe sex. Most everybody learned something about the dying process.

I visited an early display of the AIDS quilt covering a floor of the Moscone Center. A cemetery for a war, I thought afterwards, so devastating was the loss, entire squadrons of gay men shot down in their prime. There were so many ways to die of AIDS, most of them hideous. Our sexual landscape was now paired with early death by fate (as opposed to suicide). The disease infiltrated the culture with tragic love stories, nihilism, more self-hatred and finally a healing spirit as the community learned to survive. The message, like Harvey's, was again to come out, to which was added living a healthy lifestyle and working for the cause. Guidelines I would carry to environmental activism.

The Christians claimed the disease as God's punishment for the homosexual lifestyle which logically would give lesbians a free pass, but that didn't factor into their dialogue. I was getting tired of the Christians being on our case, like toxic family members, the way they were always with us, harassing us.

AIDS paved the way for the movement to take up the cause of gay marriage. Pressing issues—visiting rights at hospitals, control over a dead lover's property, protection from the hostile family members of our lovers replaced the urgency of sex. Coupling for life becoming the model of the gay community as well as the lesbian community.

Separation of Church and State?

I was glad to have domestic partnership rights. It made me feel more secure, less transitory, but gay marriage itself made me wary. I knew the Christians would take us to the mat on this, so biblical was their hatred of us. I feared a divisive abortion-issue style lock down of the political process and refused to put energy into it. Our response, I knew would suck up all our resources, monopolize the culture and ultimately co-opt our message. We would mirror the agenda of the Christians; wrestling over this into eternity. We would deserve this enemy.

All those pictures of married gay and lesbian couples beaming on TV. How wholesome we were, how much we wanted what everyone else wanted; we looked exactly like straight people. Where were the drag queens, transgender people, butch leather daddies and bisexuals? Where was the sexual fluidity and border crossing liberation from a heterosexual paradigm? Maybe I'm just old fashion—as passé as an old hippie hanging onto a faded culture of my youth.

Still, I want rights that are separate from a religious institution, inclusive of all people single or married, divorced with children, unmarried with aging parents. I want universal healthcare for all, tax breaks for multiple property owners no matter what their relationship, the right to live un-harassed no matter who we are.

My client with a gay daughter debriefed with me the week the No On 8 campaign failed. We listened to the radio show about the betrayal of the black vote.

"I worked so hard on this," he said about the campaign, "I keep thinking maybe we should have framed it differently. Was it because we called it marriage?"

"They just hate us," I said simply. He told me about a handmade sign he had seen from the opposition. "I (icon of) heart to hate."

"What difference should it make to them?" asked my mother as if their objections to gay marriage were merely a result of flawed logic.

We are the devil incarnate, I told her. My very existence as a liberated, openly gay person is as good as saying I don't believe all that crap you are spewing about sin and going to hell. You and your beliefs don't exist. Poof!

We cannot make gay marriage okay in their eyes because sex itself is a problem unless for procreation. And gay sex is the most evil of all because it is the spilled seed. Gay sex is the elephant in the middle of the room. Our culture is generally squeamish about sex, but even more so about men having sex together. How completely gratuitous. (The same could be said of lesbians, but we are relegated to porn fodder for men, harmless turn-ons, our eggs safely contained, as it were. Independent women are still a threat; they'd rather a woman be safely beholden to the authority of a man, but that would diffuse their campaign against the greater threat of gay marriage.)

No, the Christians are not rational, but queers aren't rational either. We are fabulous. As fabulous as a fruit bearing plum tree spitting its pulpy mass onto the ground. As fabulous as all manner of botanical wonders flaunting outrageous expressions of life, spilling seed every which way, every where—inside of a bird, nestled in the coat of a fox, down the drain, shrink wrapped in styrofoam—food for all comers, procreation an afterthought.

What possible scientific rational is there for queers?

I'll go with stimulating the creative juices with outrageous, bold imagery. I'll go with mediating for straight couples as the Native American berdache did. I'll go with the need for a non-dualistic perspective; heck I'll even go with nothing, after all I'm here, I'm queer. Isn't that reason enough?

The religious traditions that actually celebrate sexuality, as far as I know, are the earth-based ones. Sex as a celebration of fertility and renewal. The Priestess in the temple performing the sexual act with a ritually chosen man, for all eyes to see, so as to elevate everyone's sacred connection with the life force. Christian power sought to cut off personal access to the divine. Only priests were allowed to speak to God—a monotheistic, jealous, punishing god. All else cast into the realm of profanity. The priestess became a whore, sex the downfall of mankind, original sin licensed by marriage for procreation purposes only.

The only argument left to justify the existence of gay coupling is love. That is the argument I gave to my high school girlfriend's Christian fundamentalist mother when I was 19.

"That's not love," she spat at me thus convincing me of who was truly dangerous.

A people who will not allow others to love have something deeper at stake, possibly their entire universe. They are capable of believing that gay marriage will call out the four horses of the apocalypse. They are not going to be won over by the earnestness of normal looking gay couples. They will do whatever it takes to stop this blasphemy; this pagan weed that threatens to render them irrelevant, free the faggots, call off control of women's bodies, promote masturbation and push them down the slippery slope of theological arguments from manipulative metaphors, to misinformation, to out and out lies until their dogma poop falls into the dustbin of obsolete mythology.

Now that Prop 8 has won, we can work to separate church from state, agree that it is against our social contract, our sense of justice, to allow the constitution to be used by one group to take away the rights of another group. Some may reflect on how they will override the sex negative bias of our culture. The fundamentalists, meanwhile, deserve a backlash for having institutionalized their hate and reminding everyone of the roots of fascism. Meanwhile we queers can go back to figuring out how we can reintegrate our own diversity.

Labels: homophobia, homosexuals, politics